Decommodifying Art — A Conversation with Laura Summer

A conversation published in Lilipoh, Winter 2023

Could you start by telling us a little bit about Lightforms Art Center? How did the center come to be? What kind of work does the center support, and what are some of your guiding principles?

In 2017 a group of artists began meeting around the idea of creating a multipurpose art center dedicated to spirit and art. After many meetings, we decided to look for an appropriate space in Hudson, New York. Generous investors made this space possible, and in December 2020, Lightforms opened its doors with an exhibition on metamorphosis. The next two years were full of exciting exhibitions, including Hilma af Klint and Judy Pfaf. Lightforms was run on a traditional art center model under the wise guidance of Martina Muller and Helena Zay.

In January 2022, funding for paid employees was no longer available. Although this seemed a huge challenge at the time, I think it was actually a blessing for Lightforms as it allowed us to try out new organizational forms and to look for a group of artists who were interested in being involved on a volunteer basis. We could turn our energy towards diversity and inclusion and make Lightforms a place where everybody could feel at home.

Currently, Lightforms is a collaboration between Free Columbia (www.freecolumbia.org) and the Hawthorne Valley Association (hawthornevalley.org). Free Columbia is an arts and education initiative that runs without paywalls, meaning that all programming is available to everyone. Hawthorne Valley Association is a nonprofit made up of diverse initiatives committed to the renewal of soil, society, and self by integrating agriculture, education, and art.

Lightforms occasionally hosts Art Dispersals following a show. Can you explain what an Art Dispersal is and how this concept came about?

The idea of Art Dispersal originated with my work in Free Columbia. I am an artist, and I work in two dimensions in many media. I have shown in many venues, including galleries, alternative exhibition spaces, and one museum. I know that original work on a wall can transform a space, and from the letters I have received from the people who have my paintings, it can also transform the people who are in those spaces.

So I wondered, how can I get the paintings out into the world so they can do their work? It does not work just to give them away. It gives a message that the paintings are not valuable. But the current art system makes it impossible for most people to even consider owning original art. I wondered, can I allow people to become the stewards of my paintings? Can I ask them to take responsibility for the well-being of the paintings?

Art Dispersal is an event where we hang up original works of art and invite people to become their stewards. They can take a piece home, keep it for as long as they like, and return it to the artist if they no longer want to keep it. Stewards are offered an opportunity to make a contribution to Free Columbia, which supports the artists as well as Free Columbia.

Free Columbia has run eighteen Art Dispersals over the past ten years, with over eight hundred paintings (as well as other works of art) dispersed to stewards in Hudson, Philmont, Spring Valley, and Manhattan, NY; Eugene and Portland, OR; Los Angeles, CA; New Orleans, LA; and Järna, Sweden. In 2020 we held our first online art dispersal in collaboration with the Anthroposophical Society in North America. The work in the Art Dispersals is often mine, but usually, other artists participate as well. As the form has become more known, artists sometimes contact me to find out how to run an Art Dispersal on their own.

As Lightforms is an artist-run collective, it is up to each artist to get their work out into the world. Some artists sell their work, and other artists loan their work, but I always disperse my work. Dispersal does not work well for all artists, and many people are not interested in using this form. Art dispersal may seem too risky for an artist who does not produce very many pieces over a year and whose pieces take a long time to create. But for an artist who creates a lot of work, it’s a great way to get it out into the world onto the walls of people who want to live with it. I have found that contributions in relation to a painting have ranged from $20 to $4,000 but often average around $300 per painting.

Granted, it is an unusual way to work with art and money, but for me, it works well, and by now, I have work all over the world.

One of my missions as an artist is to experiment with decommodifying art. Today’s art world often treats art as a commodity, an investment, something to make the buyer more money in the future. Artists are often left behind in this model, unable to make a living, and most people feel that original art is beyond their means. Art Dispersal is my attempt to experiment with a model that gets money to artists and gets artwork into people’s homes.

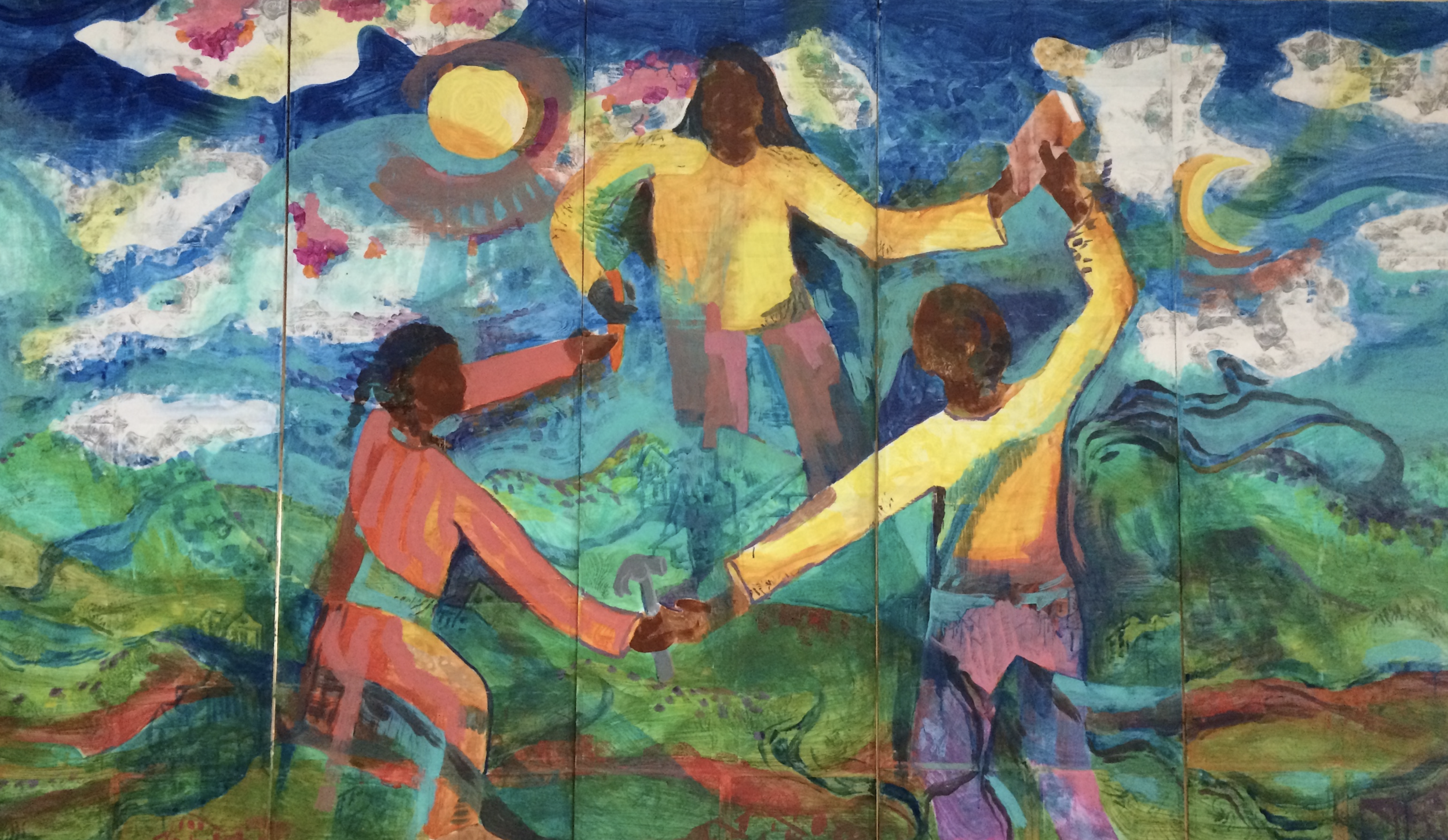

Because Lightforms is not a commercial gallery it is free to experiment with new forms created by artists. We have seen this in our “Who We Be” exhibition, a celebration of Black life in Columbia County, NY, with a unique, fully immersive approach, in our group show “We Are Lightforms,” where artists responded to each other’s pieces and created new works, in a new approach to open mic where the emphasis is on making a space where everyone can share their gifts, and in our co-working space where artists can create work together.

There are other models that can support artists and decommodify art. One such model is “Enliven the Walls,” where an institution contracts with an artist to enliven their space. The institution puts a line item in its budget for “painting support,” and the artist gets a monthly stipend. The paintings are offered to spaces on a loan basis, so artists retain ownership. Holder House, the Threefold community dormitory in Chestnut Ridge, NY, uses this model to provide original art in all of its guest rooms.

I am sure that many other forms could serve both artists and those who love to live with art.

We just have to be creative and inspired to find them, but it seems that creating new forms is what artists are so qualified to do.

Why do you think art is particularly suited to the idea of stewardship, perhaps in contrast to other physical objects?

I think stewardship is a particularly good way to look at art because art does not get used up. If you steward a loaf of bread, you basically have to eat it in order to have a relationship with it, but you can steward a painting or sculpture over your entire life, and even at the end, it is not used up. It can be passed along to someone else. I also feel that each painting has a job to do. Keeping them in my closet is like having them on the unemployment line, unable to find their purpose. So just dispersing them to a steward who wants to live with them provides them an opportunity to do their work, their work of transforming us human beings, the work of helping us to see past the material world into a realm of meaning. They will no longer be unemployed. And maybe this will be important enough that the people want to support the work.

The following are some comments that stewards have made in the past.

“Looking at your work makes me think that this kind of activity makes a more lasting impression by being in the house than not, because it does form part of our daily life.

It weaves itself into our daily imagination and emotions without being prompted by external considerations. It forms part of our daily eyes.” “It sort of felt like adopting a baby. A beautiful quiet well-behaved baby. It was as if everyone had a painting that was meant for them in the room and they had to find theirs.” “Revolutionary! Thank you for inspiring creativity.”

How could the concept of stewardship vs.ownership change how we view art and its role in society? How could it change the position of artists?

If we recognized art as essential to humanity’s well-being, we would strive to find ways to support artists and get art out into public and private spaces so that people could be inspired by and cared for by the art. German artist Joseph Beuys said, “Art is the only revolutionary energy, in other words the situation can only be changed by human creativity.”

I think that to understand this, it helps to try to imagine a world without art. Think of your favorite book, song, dance, or movie, and then eliminate it. Then eliminate all of that category: songs, books, or movies. And then eliminate all the other categories, all paintings, all photographs, all music, all dance. Suddenly you see the world without art, and that is a dismal and frightening thing.

The problem of getting visual art out into the world is different from getting music or video out. With these media, a person does not have to take the piece home. It’s easier to understand that no one really owns music; it’s there for everyone. But today someone does own music, and it’s often not the musician who wrote it or played it; it’s someone else who can promote it so that it makes money for them. Maybe it also makes money for the musician but probably not.

A musician friend told me that all of his royalties for an entire year for five albums he has released bring less than $100. So the problem exists in all spheres.

Can we imagine a world that is filled with the results of human creativity? Where walls are filled with paintings? Where the streets are filled with music? Where truth, beauty, and goodness find expression in the lives of everyday people?

What are some new things on the horizon?

I hope that in 2023 we can hire a diversity/outreach/ development coordinator for Lightforms.

This would be someone who loves the mission of Lightforms and, at the same time, loves working with people and reaching out to all the diverse communities we live within. This could take Lightforms to the next step, a place founded in anthroposophy and teaming with people of diverse backgrounds who are dedicated to the spirit and its relationship to art.

Currently, I am working with musician Matre (Matt Sawaya) and social change maker Seth Jordan to develop some new forms for releasing music that can support both musicians and listeners.

This initiative is called Love Bravely. Love Bravely’s first song will be released in January 2023. You can hear it at www.lovebravely.substack.com, and if you are moved to support this endeavor, you can become part of the very first steps of this new relationship with music.

The next Art Dispersal will be in the spring of 2023. It will have a small in-person component but will be mostly online, with pieces on paper that can be easily shipped. If you want to be notified, you can sign up on Free Columbia’s email list on our website: freecolumbia.org/newsletter

Laura Summer is co-founder of Free Columbia, an arts initiative that includes programs based on the fundamentals of painting as they come to life through spiritual science. It is completely grassroots donation supported and has no set tuitions. Her approach to color is influenced by Beppe Assenza, Rudolf Steiner, and Goethe’s color theory. She has been teaching and working with questions of color and contemporary art for thirty-three years. Her work, found in private collections in the US and Europe, has been exhibited at the National Museum of Catholic Art and History in New York City and at the Sekem Community in Egypt. She has published twelve books and founded two temporary alternative exhibition spaces in Hudson, NY: 345 Collaborative Gallery! and! Raising Matter-this is not a gallery. Laura also initiated ART DISPERSAL 2012-22, where over eight hundred pieces of art by professional artists have been dispersed to the public without set prices. She is the acting director of Lightforms Art Center in Hudson, NY. Laura teaches online and in-person courses on color and anthroposophy. Her work can be found at laurasummer.com

The Vacuum and the Plague: A Meditative Path into the Reality of the Moment

Everything that exists is bein: the house, the mountain, the tree, the car or the dog, as well as the fingernail of the hand; everything is being. From the most elementary to the most majestic, spiritual beings interweave themselves; they are, and they bring forth, what we call creation. For our awareness, their interconnections are conditioned by a fundamental law: a unity in the spiritual word is a multiplicity in physical existence, while a unity in the physical world is a multiplicity in the spirit. The being of the plant appears as a unity, the primal plant, and as the many differentiated plants in the physical. On the other hand, the physical plant, for example the rose bush on the roadside, appears as a unity, but as a spiritual reality it is the activity of the beings of the sun, earth, water, mineral, air, of life and so on. Given that a being is present wherever it has effects and that a being unfolds particular activity, the plant is a spiritual multiplicity, as is every particular physical appearance. Every “thing” is a spiritual multiplicity, a tapestry of activity in which no emptiness can be discovered. In other words: nothing exists that is not, and everywhere something exists, someone exists, is active, as a being. Non-existence cannot be found.

“In the house of my Father” there are no empty rooms. But what happens when a being does not unfold their activity? When a being withdraws and is inactive, and is not (there) as it should be? What happens to the horizons of activity that are left empty in creation? What are the consequences of a spiritual vacuum, or an actual spiritual emptiness? What is the reality behind the “horror vacui,” the “fear before the void,” nature’s dislike of emptiness and the need of classical artists to fill every empty space?

Where an activity is neglected, something else unfolds. When the apartment is not cleaned, there is chaos, when the encounter does not occur, loneliness emerges, when the word is not spoken, there is silence, when thinking is not unfolded, stupidity spreads itself out. So the “horror vacui” is real; wherever an activity does not unfold, a space is made available for another being, another activity, to grow. Someone else moves into this emptied space and spreads out their life and activity in the wrong place, in an area of life where their activity is not justified. The spiritual vacuum is a beckoning temptation for other beings to expand their horizons of action so that their rightful proportions are exceeded; that which is right and good in a particular cosmic proportion becomes monstrous when it outgrows its necessary sphere of activity: it becomes a plague. The being of the plague is that activity through which a being expands beyond its justified field of existence on a catastrophic scale. The fact that the catastrophe might serve to bring back a state of balance through a dynamic process does not make a catastrophe less catastrophic.

Covid-19 is a symptom of the present catastrophe, which also permeates our connection to the world, to truth and reality, to feeling and morality; it is a reality, a specific event, a behavior, so, a being. There is no question that this being, in its differentiated activities, has a right to exist. It is also beyond doubt that it has unfolded life in excess and mass. This “Pan-ic” (Pan means the all-encompassing), this Dionysian event has so far exceeded its place in the cosmos that, not unlike the bacchanalians, it threatens to destroy everything. We stand before it, as though before a derailed train, with the certainty that it is not easy to stop it, that it must run its course. The urgent question remains: what is the vacuum that made this spiritual derailment possible, or even necessary? What essentially didn’t happen? What spiritual activity withdrew, left us, allowing the vacuum to emerge, in which the being of covid-19 had to develop on such an extraordinary scale, without proportion?

For those who have been able to maintain some distance from the monkey dances of opinion and have been able to cultivate a deep listening to the events of the last years, it is clear that besides the painful loss of human life, truth has become the victim of this plague. Of course the truth itself cannot be harmed, only the capacity of human beings to know it, to accompany it in thought. Every day the capacity to discern between what I have come to know and what I do not know is eroding in immense proportions. With Mephistophelean cleverness, as a regressive move of counter forces within us, we have been led again into some kind of mediaeval battle of faith. It appears as if the truth is no longer accessible to the individual spirit but is a question of faith and creed. If we are proponents or opponents of vaccines, if we belong to those who believe in science or attach themselves to other theories, none of us discern anymore (or if we do only with great difficulty) between fantasies and facts, between what we know and what we believe. Of course, this process is not new, and it has been accelerating for years, but it has reached a mega-dimensionality that in its monstrosity can be characterized as Pan-epidemic.

If I approach this state of affairs without bias I realize that, at its core, this plague without proportion is connected with the question of truth and facts, with thinking and observation. To my inner eye a multi-dimensional displacement appears, one that has been intensifying for years and is now at a climax, a displacement of thinking and observation, information and knowledge. I can experience how the pandemic is not so much connected with what we do, but rather with what, in small steps, almost without noticing, we leave undone. It is we, human beings, who have created the spiritual vacuum that forces the being I will call Covid-19 into a bloated pan-ic dimensionality.

I can discern a displacement in human experience that has unhitched thinking and observation, leaving significant areas of daily perception categorically inaccessible to cognition. A sphere of perception has emerged with which, fundamentally, I am unable to connect through thinking. Here, where the activity of thinking should unfold, the possibility is absent, so an essential spiritual activity simply does not occur. Where this activity was to unfold one finds a spiritual vacuum. In order to understand this, a brief review of the connection we have with the world as cognitive beings is necessary.

The world of nature and of human creations appears to us as perception through our bodily organization. However, what eludes us due to this same bodily organization are the thoughts, the essential in things, what makes them what they are, that is, their spiritual reality. We have to re-introduce or add these to perception through intuitive thinking. Our thoughts are therefore a kind of spiritual mirroring of the aspect of things that exceeds the particular momentary perception, of that which is at their core. The thoughts in our awareness are the silhouettes, or shadows, of the activity in the things out of which they arise. In other words: thoughts are in things and inseparable from them. An oak tree is what it is because the law of oak unfolds its active thought being through it - otherwise it would be a mere pile of debris. The same is true for the flower, the bus or the mountain, as well as every single mineral. It is the active being that reveals who and what it is to me through thinking. I know the world when I connect the thoughts I have achieved with observation. Cognition is the reconciliation of the connections between things that only through my restricted, sense-oriented constitution were separated in my awareness.

Whoever has never smelled the ocean will never be able to come to the salty, moist experience through an image on a screen. If I have never seen the ocean, the being of the ocean can only be approached through analogy and the comparison of various memories. If I perceive a photo, the being is inaccessible for me, or only accessible through a detour of memory (“Even though it does not breathe, this cluster of pixels on the screen reminds me of a face; it looks like…”). In experiences that are turned into linguistic or optical representations, there is always a turning away from the thing, something already analyzed and composed, something that excludes my thinking and its connection to the thing. When I am thinking about information, photos, films and descriptions I am closed in myself. I engage a logic that very well may be in harmony with itself, but I don’t progress to a connection with the world and its creative life. I see something on a photo and I can reflect on it. Then I am thinking about a photo and not a thing. The active thoughts, which are in the things, are no longer accessible to me through observation and intuition. I can analyze and explain a photo, but it never provides the certain cognition of direct experience.

Since information is not that about which it informs me (as in, the photo of Everest is not the mountain itself), the intuitive exchange between my thinking and the world occurs either not at all, or only in reduced form. I cannot really think about the measureless information amassed before me, I can only have opinions. (“I don’t know, but I think…”). To create an opinion means that I cannot actually know, at least at the moment, and I instead provisionally form an opinion.

If, for example, I encounter more of the world online than I actually experience, then things I am informed about quickly outgrow the body of my experience and my spiritually active thinking recedes. Instead of entering a dynamic exchange between outer and inner through thinking about the world, I start to create opinions and to connect information. This is more of a soul process involving the intellect and personality than a spiritual activity. Here, where my spirit withdraws from the inspiration and expiration of the process of cognition, emptiness emerges.

The draw of this space and vacuum reached gigantic intensity through the flood of information, videos and images, necessitating its growth into pandemic proportions. There is so much that lives as information, beyond our direct thinking, that we are likely to inform ourselves rather than engage in the work of cognition. Every decision and statement made with experientially impoverished information is opinionated and thoughtless and contributes to the vacuum. The excess of pre-formed knowledge, as text, image or film, has banished our own acts of thought from the world, and where “I” should be detectable between ourselves and the things, an absence of spirit has emerged. The expansion of another, of a not-“I,” into this vacated space is the being of the pan-ic plague, it is the disease of relation between the outer and the inner.

Note:

This consequential behavior of the spirit and the world intensifies with the degree that representations of the world claim to be truth. This implies that the news, documentary film and newspapers, etc. belong to a category of representation that excludes the possibility of thinking. It is this category of representations that tempt us into believing they are transparent, that essence and reality can shine through them. Entertainment films, literary texts and musical recordings are exactly what they appear to be: artificial-artistic presentations that do not correspond to the world but to themselves and their own fictional logic. This is why they can rightly be judged as they appear. It is not without reason that we are more likely to find the truth in literature and poetry than the newspapers. We are able to form a direct judgment of a recording of a musical concert even when we are aware that something is lacking as it is not live. The truth claim that accompanies any presentation is diametrically opposed to our possibility of penetrating it through thinking. This is why, for example, Rudolf Steiner insisted he had to “speak pictorially” (“pictorially” means it is not literally true).

In any case these reflections should not lead to an alienation from technological representation. On the contrary - only when we know the rules of the game are we free to play.

Radio Interview: "Pathways to Aesthetic Education and Contemplative Inquiry"

On October 12th Nathaniel Williams was hosted by Hélène Lesterlin and Aja Schmeltz for a conversation about Good Work on Kingston Radio. You can listen to "Pathways to Aesthetic Education and Contemplative Inquiry" and other interesting episodes here.

Final Report on the Current of Goodwill

a social-art project within the M.C. Richards Program

“If my Mother had four wheels and a drive shaft she would be a touring bus.” -Rudolf Steiner

Art allows us to entertain things that are “not real”, and this opportunity can inspire us to see conventions in new light. This was the idea of the Current of Goodwill, a social-art project of students from the M.C. Richards Program cohort 2020-21 and the Hudson Valley Current, that is now complete. It was not intended as a project that would demonstrate a shovel ready alternative to conventional money systems, but as a creative act that could allow new experiences and insights on money and economic exchange. In the process hundreds of moments were created when a currency evoked an act of thanks, learning about the Hudson Valley Current and Free Columbia. Through this project a group of students were introduced to monetary orientations inspired by Rudolf Steiner, in the context of Marx, Friedman and Raworth, among others. Each completed card, or unit of 50 HVCs, was ultimately directed as a grant to individuals and initiatives dedicated to the common good.

100 cards, each worth 50 HVCs (equivalent of 50 USD), were created. Assembled together they created a picture of interdependence, giving and receiving.

In order for them to be redeemed as a grant to a local organization each card had to make a journey, which involved passing between five people and being returned by mail. Of the 100 cards that went out, 25 made the return journey. 1,250 Hudson Valley Currents were dispersed according to the choices indicated on the cards. In September of 2021 the grants were awarded.

450 was earmarked for “Arts and Education” and awarded to THE ART AFFECT

250 was earmarked for “Addiction Recovery” and awarded to SIMADHI

250 was earmarked for “First Responders” and awarded to THE PHILMONT FIRE COMPANY

150 was earmarked for “Community Centers” and awarded to TILDAS AND THE HVC

150 was earmarked for “Food Pantries” and awarded to SEASON DELICIOUS

Aesthetic Education for the Anthropocene

Aesthetic Education for the Anthropocene

By Nathaniel Williams

Maryline Robinson, Adolf Portmann and Emily Carr

Free Columbia’s M.C. Richards Program is a site of action research, a college level initiative aspiring toward aesthetic education and contemplative inquiry. It is small and as humble as one would expect, and it is a fledgling, just entering its second year. This essay is inspired by the ongoing work in the program toward a contribution to Mary Caroline Richards’ question of whether one can develop “…practices to strengthen and enliven living images, in contrast to mechanical and life-destroying images? And how may thinking itself be taught in ways that promote life, rather than estrange us from it?”.

Who needs aesthetic education? This archaically colored phrase could easily bring up associations of uselessness, or of the aloof enjoyments of a privileged life. It might be associated with the beauty parlor or with art appreciation seminars at liberal arts schools. Aesthetic education can be understood in a much more comprehensive way, as important for everyone. One reason aesthetic has an archaic sound is that it is derived from a term in ancient Greek. The term meant the perception of things with the senses. In the dentist’s chair and the hospital anesthetics are used to block perception and feeling. Aesthetic experience is as common as memory, dreams or thought, we all have it in some measure. It is the foundation for a trusting, open and intimate experience of life. Our ability to live with the wonderful, special forms of sensible experience, to perceive the particulars of life, is aesthetic. It is also connected to our experience of qualities, moods, and intangibles that emerge as we move through life. It is not only sense perception, but en-spirited, en-souled perception and imagination, connecting us to our natural environment and other people. Aesthetic experience unfolds when we watch a friend approach and feel how they might be doing, through how they walk or stand, how they address us with movements of their voice. Sense perception is suffused with soul and mind. We might find ourselves inadvertently staring at someone, at some feature of their face, and the slightest change in the feature suddenly ignites uneasiness as a mere what becomes a who. We look away. We see a deer, ears stretched up, erect and head alert, our presence leads to the sudden cocking of the legs, ears tilting back, breath quickening; another sentient being. Climbing a northern mountain in autumn, the forest’s bronzes and reds fade into many evergreens as do the sounds of insects and birds; bright lichens and mosses fill the forest floor. The stones are loudest in silence. Water has washed the stones clean along stream beds and white waterfalls rush, sounding like light.

Generally speaking aesthetic education is associated with the arts and humanities today. Yet it is easy to see that aesthetic judgement is a central part of our social and political life, our relation with other beings and the various regions of the earth where we live. Our first associations are misleading. Aesthetic education is not necessarily about privilege, aloof art appreciation courses, beauty school, or even of the humanities. It is more foundational. It is connected with our ability to participate in ecological, interpersonal, social, cultural and political life.

Perceiving with our senses is an activity that can be strengthened or atrophied. It may seem odd to suggest that our ability to unfold rich, pictorially constituted understandings is under threat, when we are increasingly surrounded by images from digital devices and inventions. The digital revolution is a watershed that will increasingly deserve careful attention and critique, but in this essay I follow another path.

The Swiss zoologist Adolf Portmann suggested a general approach to exploring aesthetic experience that I will contribute to here. In an address he delivered on biology and aesthetic education Portmann differentiates between two core human capacities. He calls these the aesthetic function and the theoretical function. He suggests recent centuries in the Occident have “emphasized the value of scientific rationality and the valorization of the quantitative, shifting qualitative experience to the margins.” The feats of the theoretical function are all around us, they include the technological revolution we are in the midst of. They stand before us with grandeur and power. We also know they are heavily capitalized, at work defining our current lives and immediate future. In this essay the task is to look toward these powerful tendencies and achievements from a critical perspective, focusing on their anesthetic affects. The following characterizations and critiques of the functional capacity are not an argument for irrationalism, but an argument against hyper rationalism.

Portmann characterizes the theoretical as “…{t}he activity that employs above all the capacity of rational thought, that employs and utilizes scientific analysis, and which leverages mathematics in general. This activity quickly leads the thinker beyond the immediately given world of sense experience and especially loves to dwell in the realm of numbers and quantities. This activity involves striving to transform the qualitatively given world into quantity. Once tones are traced back to vibrations and colors are traced back to wavelengths, a certain contentedness sets in, a victory has been achieved. This is said without the slightest irony, as an attempt at a sincere characterization.”

Living into this orientation we can make some observations ourselves. In the theoretical tendency one can make out a sense for an absolute, calculable coherence. It is a kind of lawfulness that we sense as “behind” normal experience. When we turn toward this coherence, however, it is peculiar in the way it is static and immobile. We feel changes can be made to a part that superficially effect the overall frame. There is a weighted sense of sameness, and a diluted sense of particularity. Re-ordering the whole is of no significance. It is different, but the coherence is the same. The victory that Portmann characterizes above, when qualitative particulars are transformed into the calculable, culminates in a wholeness of this type. It is a certain sense of comprehensive judgment. Perhaps the most important observation we can make, however, is that we are not a unit in the equation, that we ourselves are excluded. This need not be articulated to have an effect on us. There is a widespread subtle, general cognizance of this. We feel we are privy to a phantom of wholeness. How can anything be whole that excludes our being? This exclusion marginalizes the felt value and gravity of much of daily existence. Think of our experience of the vivid connections or tensions with people, ethical energy that animates our actions and goals, or an exquisite impression of the spiders web covered in dew, lit by the morning sun. Our theoretical function engages to transport all of these into quantitative models of coherence and pattern. Generally we sense this process of translation is the process of knowledge, and first person, qualitative judgment as rightfully marginalized along the way. But we feel on this journey of knowledge, we arrive with our theoretical vehicle but we have lost ourselves along the road. Spookily the engine of transport delivers a vehicle with an empty cockpit. Marilyne Robinson offers this characterization in The Absence of Mind, “A central tenet of the modern world view is that we do not know our own minds, our own motives, our own desires. And – an important corollary- certain well-qualified others do know them. I have spoken of the suppression of the testimony of individual consciousness and experience among us, and this is one reason it has fallen silent. We have been persuaded that it is a perjured witness.”

The contentedness described by Portmann will be familiar to all of us. In this essay we are not focusing on the joy and achievement accompanying it, instead we can focus on this subtle lonesome hue. Its basic character tends towards defined functions and units that can never correspond with a being who is able to respond and relate to us, or a world in which we could actually live. It excludes our basic experiences of both selfhood and life. This is why there is an unconscious feeling that comprehensive translation of existence into theory of this type cannot result in reconnection. While sensing theoretical interconnection of this type on a sublime scale (say the universe) can awaken reverence and awe, this reverence is at the same time tinny, for its finitude is always only slightly veiled to the heart.

This quasi-wholeness is an engine. If our lives are weighted toward the theoretical, the isolation it can produce makes us thirst for movement, variety and speed. It is the internal combustion of a schism. This spark can lead us to high velocity, high definition images in games, movies and series, social media, general surfing or digital sex sites. Yet in the end, we feel we are building bridges with air. The schism can also lead us to drugs and religion as pathways to escape our one-sided mental life. Drugs take us somewhere blindfolded, only to dump us out sometime later in a ditch with no idea how to make the journey again, bruised and weaker than when we set out. Religion opens up spiritual visions and images for us giving meaning to existence, and often aesthetic ritual, yet it is the rarest of occurrences to feel oneself able to travel from the alter to the forest, and certainly not to the “prestigious” halls of the university. Drugs seem to give us what we want on the terms of the loan shark, while religion often treats us as orphans, even though they cannot take full custody, nurturing us only on Sundays while demanding we renounce our natural parents, with whom we spend the rest of the week.

Despite this discontent, we often sense that our theoretical work is objective, neither good nor bad, actually neutral. This feeling is not arbitrary. It reveals important characteristics of the theoretical function and quantification. Still, when we look at the theoretical function in context we see it is not neutral, that it does privilege certain values. The theoretical function unfolds through quantification, calculation and functional manipulation, and in turn we shape the world in this spirit.

During our daily rounds aesthetic experience flares up, with sustenance, important contours are washed out and alive on the edges, with fissures bubbling with interiority and life. Portmann suggests this is connected to the “… striving of many humble people toward joy and happiness. As educators we have to take most seriously that the most simple and genuine sources of joy are drying out for countless people. The natural foundation for joy, the ability for rich and spontaneous experience, is eroding.” These indigenous capacities do not require techno-prosthetics or chemical crutches. Adolf Portmann characterizes the aesthetic function as, “… leaving the primary impressions of the senses intact, retaining the original, unique, qualities of form and line, color and sound, smell and touch … all spiritual/mental activities have their point of departure in these primary experiences. Whereas the theoretical function works to transcend these qualities and to replace them with measurable units, the aesthetic function engages these primary sources of spiritual/mental life with trust, building on them, creating images and truth.”

Acts of qualitative embodied judgment are minor miracles not based on calculation. In these judgments impulses, melodies and movements are moving. The aesthetic capacity is present in our naïve, attentive, embodied surrender to perception, feeling and understanding. It is an orientation we adopt when we listen to someone through words, tone and body language while suspending definitions. It is hospitable to surprise and revelation, it waits and listens, it anticipates singularity. A bronze rose color on a book cover opens into a space of contentment, warmth and kindness while the dark brown of the decaying black walnut shell in late August opens into a vast, sublime and earnest field. The white pine, surrounded by maples and oaks, makes an impression combining ocean spray and feathers, light and delicate, festive and noble. The Silhouette of the cedar trees in the north country suddenly reveal a gentle and introspective atmosphere set against the bodies of hemlock. These dynamic perceptions can be intensified into works of art. Charles Burchfield was want to compose word pictures on the back of his paintings. On August 12, 1917 he wrote, “THE AUGUST NORTH: In August, at the last fading of twilight, the North assumed to the child a fearful aspect (that colored his thoughts even into early manhood). A Melancholy settles down over the child’s world; he is as if in a tomb. He thinks all his loved ones are gone away, or dead; the ghostly white petunias droop with sadness; un-named terrors lurk in the black caverns under bushes and trees. As the darkness settles down the pulsating chorus of night insects commences, swelling louder and louder until it resembles the heart-like beat of the interior of a black closet.”

There is something epiphanic about this form of judgment, wherein the distinct feeling of comprehension unfolds and flashes up with a sense of unbounded life. There is a tendency toward wholeness, yet one that is open and qualitatively mobile. Compared to the quasi-wholeness of the theoretical function, these strike us with life, subtle delicacy and sublime drama. Art can possess these tendencies in an intensified portion. If we are accustomed to moving through with a theoretical attitude, we pass by so many possibilities of judgment. We may, however, find ourselves deeply struck at some point by a simple work of art. Works of art have traditionally been shaped with a special care for perception and pictorial power. Images, moods and ethical movements are invited and tended to as active presences. The artist greets them with hospitality, and makes room for them.

Kanō Tan'yū, Landscape in Moonlight 166

Water emerges, foreground, yet a movement moves from top to bottom. The light of the sky is also a broad field of moving moisture and clouds, and the moisture opens the back of the mountain that threatens to close itself off. A boat is on the water where we float. The parts of this world transform into one another, all receiving themselves from the greater whole. The parts are not strictly separated and defined, yet they are specific. They pass into one another in an imaginative circulation of transformation. When we focus on a part, it is never severed from the whole. Art, as illusion, is lifted out of the “real” yet it feels intimately connected to reality. Cheng, the Sinologist, suggests a painting teacher leads a student to “… the creation of an organic composition in which the full embodies the substance of things and the empty the circulation of the vital forces thereby joining the finite and the infinite, as in Creation itself.” Chan art is not a definitive orientation, we can find kindred approaches in Burchfield’s practice and in the works of Cezanne and Emily Carr. These artists participated with their living environments toward the emergence of these vital artifacts and images.

There is an epiphanic dimension to aesthetic judgment, yet images are connected through rhythms; they can make a strong impression and then recede, only to come again changed. One can feel one “knows” a work of art after one encounter, but this is a habit taken over from the theoretical attitude that possesses truth. We may dwell on a dazzling echo, but we will find that the notion of our possessing a picture empties it. This is a remarkable characteristic of being alive, of making visitations. We can think of Cezanne’s attempt to capture his living motif, which he could never capture but only encounter, leaving traces of a face as a result.

This is all too easy with art. We need not fight to recognize these experiences. We still look at them like Nietzsche’s leafy oasis in the desert, they make life tolerable. But what of the desert? The all-powerful habits that relegate aesthetic judgment to the arts and humanities and theoretical judgment to the sciences need to be challenged. Aesthetic judgement, a misfit figure in science, has increasingly been shown the door when trying to attend the academy. Portmann describes how the naturalist who approaches the world aesthetically has come to be seen as an awkward ancestor of today’s scientist. This is deeply concerning when we think that it is the sciences that we increasingly turn toward to establish our connections to our natural environments. “The natural forms that surround us are a treasure chest of riches, yet how few sense the joy awoken by the variations of autumn’s colors, joy that can be ignited by one single maple in a city. How few know of the source of joy that is generally available in the fullness of leaf forms, of fruits, the flight of birds and their song? Who notices that every mother of pearl setting of the sun is a festival, every glance through the sunlit yellow leaves of the beech tree into the cool blue sky a drama, that from these simple joys of perception it is possible to ascend to dizzying imaginations of worldly experience?” Do we practice science in a way that we can experience the earth as a treasure in this sense? Or is it simply a “natural resource” to be understood and used in the spirit of calculation, control and domination? What kind of natural science might counteract this anesthetic tendency?

J.W. v. Goethe, Mary Caroline Richards and Craig Holdrege

Throughout his prolific career Portmann pioneered a research method to expand empiricism using aesthetic judgment in biology. He realized that if you are always looking for functions when you try to understand elements of an organism mysterious facets of their existence are rendered invisible. To look at the forms and movements of animals as expressive, pictorial presentation, requires suspending the functional approach and employing aesthetic apprehension. This reveals what he called the “expressive display” in nature. Aesthetic judgment reveals interiority and sentience. He articulated a distinction between the open and visible formations of the body that required this approach, as opposed to the internal and hidden, such as internal organs. This empirical approach moving between the dynamic of the physical and interiority has the effect of reclaiming a portion of those experiences that aesthetic judgment can offer us with full consciousness. The gravity and reverence of Portmann’s writings on animal’s leads to a realization that sentience is a foundational and observable mystery of our existence. Through this aesthetic method animal sentience is imbued with the gravity of the real and brought out of the epi-phenomenal shadows (or perhaps it is us who are brought out of our abstracted separation). It ushers the sentient life of animals back into the universe, and shows how mysteriously sentience is interwoven with the formation of certain facets of the physical body.

More recently Craig Holdrege has developed filial investigations in biology, building on Goethe’s delicate empiricism. These culminate in aesthetic ties to organisms through the method of “portrayal”. Holdrege’s studies involve careful empirical tending to the parts of organisms with an eye for how they express the life of the whole. Each part is not closed off as a fixed function that is thought of as a specialized wheel in a machine, but expresses the whole in a unique way. What is remarkable in Holdrege’s work is how he turns towards parts without losing the background of context and wholeness. He shows that just as we can focus on an element in a painting, or a refrain in a piece of music, while sensing its embeddedness in a whole, there are biological research methods that attain the same. These methods are disciplined and distinct even while related to artistic appreciation and creativity.

Both Portmann and Holdrege draw significantly from Goethe and his orientation in science. Goethe, famous for his literary achievements, saw his scientific work as more significant. He occupies an important position in the history of phenomenology. The foregoing may prepare us for a glimpse of Goethe’s importance. But we have to push back against the conventions and habits of the “two-cultures” that seem to place the natural sciences and the humanities in opposing worlds. Without effort on our part to understand aesthetic knowledge practices in the natural sciences we are bats in the midday sun. Goethe’s work did not lead to “theoretical” explanation in the sense we have described above as theoretical, but to aesthetic theorems. His search for “primal phenomena” involved developing aesthetic judgment into scientific insight. Unlike artistic activity, Goethe’s scientific orientation involved creating long series of sense perceptible observations and experiments that culminated in phenomenal theory, or in the words of Arthur Zajonc, facts as theory. Theory’s culmination was perceptible, yet not as a case to be explained by a general rule. In physics his color theory still stands out as a watershed moment, where a science that can lead to understanding while cultivating qualitative connections to our own experience emerges. Georg Maier’s research in optics offers a more recent example of this scientific culture in physics.

We know today that this is not only about personal joy or a “romantic” view of nature. Our moment reveals countless ways we are destroying the foundations of life and we quickly come to ask how far the ecological crisis is at root a cultural crisis? I am convinced an expanded notion and movement for aesthetic education is one part of the solution we require. I once took an undergraduate level class in Environmental Science wherein the author referred to ecology and the “Wisdom of Nature”. In the context of the textbook, that contained nothing but models of “mechanisms”, the sad impression this term made on me is unutterable. While there are obvious reasons that theoretical culture is most at home in the natural sciences there are increasingly obvious dangers to its hegemony. We understand that we are interdependent as beings and we share a moment on this planet that requires a wisdom of the particularities and existential interdependence of our existence, which our theoretical culture cannot offer.

Aldo Leopold, of particular importance to the ecological movement in the USA, once wrote: “All I am saying is that there is also drama in every bush, if you can see it… When enough men know this, we fear no indifference to the welfare of bushes, or birds, or soil, or trees… We shall then have no need of the word conservation, for we shall have the thing itself.” Here Leopold presents the idea that our ethical action is connected to the quality of our connection to our habitats. Our awareness of our natural environment, largely informed by our theoretical culture and muted by our technological life circumstance, is knowledge numb to the terrestrial that can be held dear. In a decisive moment for our limited and interdependent planet we live in thoughts of infinite translation as calculation. We find ourselves at the peak of a legacy of a theoretical culture that can be traced back at least 500 years to the continent of Europe. It has worked for centuries to translate qualities of experience into quantitative fields of calculation, subtly tending toward domination, control and alienation. This is now our superpower, looming over our increasingly atrophied aesthetic capacity, when it is the latter we need more than ever in natural science and our practical ethical lives. If the ecological crisis is going to be faced voluntarily and collectively, and not through ecological or public health tyrannies and dictatorships, there is a significant task at hand- The expansion of the notion of aesthetic education to include the natural sciences, and its energetic and widespread implementation.

1 Adolf Portmann, “Biologie als Aesthetische Erziehung” in Biologie und Geist. (Suhrkamp, 1968). His address has only grown in significance. In this essay I follow his lead in making a general distinction between theoretical and aesthetic capacity, though I develop this along different paths.

2 Ibid. 250.

3 Ibid. 248.

4 Rudolf Steiner develops a powerful characterization of this unconscious feeling in an address given on January 19th, 1924, published in the collection Anthroposophy and the Inner Life: An Esoteric Introduction (Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015).

5 Marilynne Robinson, Absence of Mind: Dispelling of Inwardness from the Modern Myth of the Self (Yale University Press, 2010), 60.

6 See the first part of Hans Jonas’s Philosophical Essays: From Ancient Creed to Technological Man (Prentice-Hall, 1974)

7 Adolf Portmann, “Biologie als Aesthetische Erziehung”, 256.

8 Ibid. 246.

9 François Cheng, The River Below (Welcome Rain, 2000), 109.

10 Adolf Portmann, “Biologie als Aesthetische Erziehung”, 256.

11 See Craig Holdrege, “Doing Goethean Science.” Janus Head 8, no. 1 (2005): 27–52, The Flexible Giant: Seeing the Elephant Whole (Perspectives 2. Ghent, New York: The Nature Institute, 2005) and The Giraffe’s Long Neck: From Evolutionary Fable to Whole Organism (Perspectives 4. Ghent, New York: The Nature Institute, 2005).

12 Arthur Zajonc. “Facts as Theory: Aspects of Goethe’s Science.” In Goethe and the Sciences: A Reappraisal, edited by Frederick Amrine and Francis J. Zucker, (Dordrecht: D. Reidel Pub. Co, 1987).

13 Georg Maier, An Optics of Visual Experience (Adonis Press, Hillsdale, NY. 2011)

14 Aldo Leopold, The River of the Mother of God: And Other Essays by Aldo Leopold (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 263.

An Interview with Craig Holdrege

by Eve Hindes and Stefan Ambrose

Lightly edited by Nathaniel and Craig. Transcribed by Stefan. This interview was conducted during Craig’s Fall course in the M.C. Richards Program and focused on the book Do Frogs Come From Tadpoles by C. Holdrege, (Evolving Science Association, 2017).

Eve Hindes [EH]: Thank you Craig for coming to talk to us today.

Craig Holdrege [CH]: Glad to be here.

EH: You are an educator and author, phenomenologist and Goethean scientist, as well as a parent and person in wonder and awe of the world, and you can really see that in the way you’ve been teaching us about all kinds of creatures and their environments in the last couple of days, as well as this piece of writing you’ve done here. One of the first questions we have for you is: When did you first fall in love with frogs?

CH: I don’t know if I’m in love with frogs.

Stefan Ambrose [SA]: Sounds like you’re in love with frogs.

CH: I’m definitely fascinated by frogs. It’s kind of hard to say, I don’t actually know. When I was in college and had to dissect a frog, I wasn’t in love with them. I mean, I did it and I learned quite a bit about muscles, but that frog wasn’t really a frog. Later, in teaching zoology as a high school teacher, the metamorphosis of the tadpole into the frog became interesting to me when I realized: They don’t lose their tail, they digest their tail. I thought, okay this is strange. So it was in learning about the metamorphosis of the tadpole into the frog that I started to become really interested in them. Then it kind of waned; I’ve always enjoyed seeing frogs, and having moved here you have all kinds of frogs in the spring—early spring peepers and the wood frogs that are heralds of the spring. The chorus they make in the evening in March and April is amazing. I started observing more. So it was a gradual process. Not gradual, it was sporadic. I never really focused again on frogs until I started doing the research for this booklet. That was a number of years ago. Five years ago or something like that.

EH: Just for everyone here, I’m just wondering if it would be alright with you if I just give a little description of the tadpole becoming frog. And feel free to jump in at any point if I misspeak or if you think that I have left out something important.

CH: Please.

EH: Now it is fall and the frogs are doing their thing, but in the spring, for all the people here, imagine you’re walking here in the spring, and it’s still pretty cold, and things are just starting to appear and come up from the ground, and the bodies of water are beginning to thaw. You may come across a pond at this point. When I was little, it was great fun to go to the ponds and to find these globs on the edges of the pond, there’d be these big chunks of goop, and the game was to find the biggest one. You can imagine you go to the pond, and you find one of these, and maybe you lift it out of the water, and you notice this glob is actually a lot of small orbs, and in the center of each orb is a smaller dark, almost black, orb and you’ll set it back into the water. Maybe you’ll go on another walk a couple of weeks later, and you may find the same glob, but there’s no longer the same orb in the center, but in the water you’ll see from a couple dozen to a couple hundred of these small tadpoles in the water. They are very fishlike. They have a spherical body, and a mouth and little eyes on the sides of their head and a finned tail, and they move very quickly. and they’re living into their environment and feeding on plant life. Around here I think all frogs feed on plant life, but that is not the case for some of them. As the water warms, a few months go by, and a good deal of tadpoles stay in the form of a tadpole; for some it is up to two to three years. Then the frog will begin to appear, coming out of the tadpole. And it’s amazing, because they don’t lose the tail, as you said, it gets sucked in, digested into the body, and they rebuild and recycle their entire bodies to become this frog. And the frog, as you know, makes noise, yet the tadpole doesn’t have vocal cords, and the frog will make a whole chorus of noise, so it also hears. It’s developing ears and vocal cords. The eyes become bulbous on top of the head, and they start developing hind legs, having four legs, and the tail disappears into the body. It will begin to eat things other than just plant life, like insects, and for that it will need a tongue and a whole new digestive system. Which is insane! Because the big question is, how and why does it do this?

Towards the end of the first chapter you talk about how science tries to separate out this “activity.” They will point out that “It’s just the DNA that’s doing it” or “It’s the hormones!” But you really go into the fact that all creatures that are developing will have hormones and DNA but no tadpole will grow up to become a horse or a cow or anything like that, it’s going to become a frog, and emerge from this tadpole. So, I’m wondering, why do you think in science they separate out this activity? What is the point of trying to separate out the environment and activity, instead of viewing the frog as a being in relationship with its life process and environment?

CH: That’s an interesting question. It’s a fact that when you study biology, physiology, and developmental processes today, people raise the question—and you’re supposed to think in this way—what causes something to happen? The cause needs to be something that you can determine, that without it, the process doesn’t happen, or if you change it, the process goes differently. These are called in biology today the underlying mechanisms or a mechanistic explanation. There is an urge that has arisen in the history of science, in modern science, to look for causes in this way in biology. It’s almost taken for granted that this is what science is. It’s presupposed that if you’re doing biology, that’s what you’re doing. You’re looking for the causes, and the causes are discreet physical entities. One imagines DNA or thyroid hormone as something that is in the organism and when the genes are active in a particular way, or when the thyroid hormone is secreted, they initiate the process of metamorphosis in the frog. And, I don’t think anyone could deny that and there have been lots of experiments to show that. Scientists then talk about causes.

It’s also the case that thyroid hormone does not have the same effect in different organs of the animal. So, there is always a sort of conversation with itself, where a substance arises, and in that relationship some organs do this and some organs do that, all in relationship with the fact that this is now an organism that is in transformation. It seems to me that the search for causes limits our understanding. You’ll find interesting things, but, what one finds becomes for me part of the overall picture of how something develops. Just because you can manipulate metamorphosis by changing the hormones does not mean you understand the integrated nature of the transformation from tadpole to frog. To understand that you have to look at all the phenomena in their interrelations, otherwise, for me, it is not understanding. It is the ability to manipulate. And, those are two different things.

SA: And it sounds like it comes to being because of its relationship to the environment, naturally. Even if we can use thyroid hormone as some causal agent, to manipulate or cause transformation, that doesn’t mean that we’re going to understand how this arose through time and space, this being in relationship to its environment.

CH: That’s right.

EH: I think you touch on that when you talk about a desert frog of some sort that has tadpoles, and some of them, from the same mother, will become carnivorous and feed on tiny shrimp.

CH: In the desert!

EH: Yeah, in the desert! There are shrimp in puddles and some of these tadpoles will become carnivorous and feed on these shrimp, and sometimes other tadpoles of the same family. And if there aren’t enough shrimp in the pond, or the body of water, that same tadpole may change its diet and go back to eating algae again.

CH: And it changes its whole form too. If they start feeding on shrimp they become different from those that start feeding on algae. It’s the same species. There is a remarkable plasticity in relation to the environment that they’re living in. That’s an extreme example of very interesting frogs that are called spadefoot toads for some reason. They live in Arizona and northern Mexico and places like that. They live at least nine months under the ground as adult frogs, usually in dry areas, and when it gets a little bit wet they come up and lay their eggs—quickly. All this happens really fast in a puddle that’s going to dry up soon. So, it’s a remarkable adaptation to circumstances.

EH: That really touches on the relationship the frog has to its environment. If you were to look at that from the perspective of hormones or DNA, there’s not really a solid explanation for that. It seems it’s really about the tadpole and frog as a being, and how it exists and will be changed at all times by its environment.

“Scientists feel that what they call “causes” are explanations of the phenomena… That’s what they call an explanation? It doesn’t satisfy me.”

CH: And certainly you could learn something by looking at the hormones, by looking at the DNA. I’m never against that kind of inquiry. Because you found x, y, or z, and you change one of those factors and the process changes, does not mean you are understanding the whole process. Scientists feel that what they call “causes” are explanations of the phenomena. For good or bad reasons, this has never made sense to me. It never made sense to me, from ninth grade on; that’s when I remember thinking about this for the first time. That’s what they call an explanation? It doesn’t satisfy me. There is an interesting issue there: What we feel to be adequate as an explanation. I speak more about understanding. It starts when I feel like I’ve entered into the web of relationships to a degree, that I get a little bit of a sense of what’s overall going on. Of course not everything, but something.

SA: Right, and this leads into the next section of the book that was for me really riveting. You give this great portrayal of the frog, which seems distinct from other kinds of literature that might analyze the frog in a reductive way, and one might think, “How have you, and others, come to this way of being in relationship to the frog, such that you begin to perceive the activity?” What are these interrelating factors that actually make a thing what it is, that create and define metamorphoses, give the ability for something to metamorphose? As opposed to saying, “The thyroid hormones have caused this.”

You say at the end of the second chapter: “A science of beings moves beyond certain habits of mind that constrain our perception and understanding, it requires a different way of researching than is prevalent today. When nature becomes a presence and we have been touched by another being, we also honor that presence, that being. This connection forms the basis for greater insight, and importantly, for an ethical relationship to the natural world. A science of beings is a science that connects.”

I was wondering if you could say a little bit more about the role, and the necessity, of this intimacy in connection to the beings that we’re studying, and especially to the 7-fold process in that chapter that you describe as a biology of being? This seems like a paradigm that has these incremental layers that bring us into this form of relationship, this form of connection. Why is that relationship and connection so important to a developing science?

CH: It’s an interesting question, and not so easy to answer. While you were speaking, I was thinking: There are people who are in one way very materialistic in thinking about things, really dedicated to seeking cause-and-effect explanations, and they have the most warm-hearted relationship to animals and plants, and are proponents of biodiversity and really good people. Right? And, sometimes I feel a little bit of a disconnect between their thoughts and their feelings. Maybe they have a greater intimacy with animals than I have, because they’re field biologists and are always out there with them, and love it, and that’s great! On the other hand, if you ask them to explain the things, it's as if the animal turns into a complex mechanism. That discrepancy always felt wrong to me. I felt I could not see the things the way they are if I make them into a mechanism. I don’t deny that people who have the more mechanistic view can’t have a relationship. But the relationship is not enough. That’s interesting, right? It’s not enough. Certainly, it is a presupposition to be a good person in the world—to honor the other. It is really important! But then: Can I honor it to a degree that I’m really willing to transform my way of knowing to adapt to the way the creature is showing itself? Or am I not doing that because I’m imposing a certain framework on it? I think that kind of sensitivity is what’s key. That’s why in some contexts I speak of this approach as a dialogue, as a conversation. You are listening—not literally—but you are listening to what’s trying to show itself there, and then you’re adapting your way of knowing to what you’re discovering. That’s an ongoing dialectical process that you engage in. You are becoming different, and your way of knowing is becoming different as you’re engaging.

SA: So, maybe not step by step, but as a first principle, there’s this engagement. You are getting to know a being, you’re seeing it, you’re seeing its activity, you’re seeing its form. And then you begin to free yourself, the second principle, from the mental constraints, the boundaries, the things that we’ve predetermined, so that you can go back and engage with it again. To see more, see a little bit more. Then you begin to picture in your mind, a third principle. What is this being? So it begins to live in you, internally we start to develop, in this case, a “frogness.” So that each time we come back to this being of the frog, we get to see a little bit more because, in a way, we’re beginning to speak its language. Then we begin to compare. In this chapter you also compare the frog with the salamanders, the caecilians.

CH: The caecilians are wormlike amphibians that are quite strange, that you’ve never seen—and I’ve never seen—they are described in the literature.

SA: I was reading this and was like: “Where do these exist, I don’t think this is real.”

CH: They’re evidently real!

SA: So you begin to compare, because by comparing the frog with other beings in the same family more and more distinctions are beginning to pile up. We’re developing this memory of what it means to be a frog. Then the fifth principle, intuition. The intuition that begins to reveal things about the animal that we couldn’t have seen if we were just studying the mechanisms.

CH: Yes.

SA: And that feels really important and related to what you were saying—that an intimacy to the frog develops, like “I love the frog!” This isn’t quite enough. When we begin to actually speak the language of the frog, and intuit the frog, we begin to know more about the frog. And that becomes a science that instead of getting deeper and deeper mechanistically into what it means to be a frog, we begin to intuit the activity, things we couldn’t have seen before. And then we have the ability to portray it, another principal, for others, so they can access these intuitions for themselves. You mention that even if we portray a being, that doesn’t mean that through a portrayal that we’re actually giving someone knowledge, or that we’re giving someone the experience of what a frog is. We’re just creating almost an architecture, or an experience, where someone can, of their own volition, of their own capacities, decide for themselves what a frog is. And you say this requires some finesse—how to portray something well. And then, we can go back—not just as scientists and people practicing this method, but also as someone who has maybe read one of your portrayals—go back to the frog again and see more and more. So this really is a developing process. It sounds like in the traditional mechanistic scientific community there are, gradually, more who are seeing the limitations of strictly reductive research, but still something is missing.

CH: Yes, and I think a lot of scientists who are doing this kind of work carry these things that I’m trying to work with in a more unconscious way. They’re synthesizing, they’re seeing relationships, they’re seeing things in a more holistic way than they are perhaps articulating—and that they’re, very frankly, allowed to articulate, right? If you want to get a scientific article published, you have to do it in a very particular way. Otherwise, you’re gone. If you’re going to be an academic, you’ve got to publish, or you will perish. And, so, you’ve got to fit a specific form. And there are so many wonderful, really incredible people studying animals and plants around the world, that are not only full of heart, but are also full of observations, and the understanding of relationships. Unfortunately, there is a superstructure throughout the scientific community, and through what has become tradition, that everything has to be interpreted in a certain way if it is going to be accepted by the community. So there’s a certain sadness that I have about that. But I don’t want to be critical of the individuals doing that work, because they’re doing good work. I mean, you can have your questions, for example, about animal experimentation and all these kind of things. I have my big questions. You know, what are we doing to animals in laboratories to prove something, messing around with their brains, or this, or that? You can have real questions about that kind of work.

EH: Why do you think it’s important for this way of viewing animals as beings to be, I guess, permeated into the world of science, and what do you think the effects in a societal way would be if scientists were allowed to approach these matters with heart first?

“This turning towards the concrete in the world and training our capacities to be able to deal with complex, dynamic situations is, I think, where we need to go as humanity.”

CH: I think we would simply become better and better at always understanding things in their dynamic relations. That’s what it’s about. Ecology as a science is the science of relationships. And yet, it has become, for example, so data driven. Where you’re starting with such high level abstractions, and then the only things that you can say relate to data that is deemed statistically significant. So, you have a statistical analysis of something, and say, “well, that may be a trend.” A statistical trend towards this or that. You can’t say anything really about the individual case. Right? And so this turning towards the concrete in the world and training our capacities to be able to deal with complex, dynamic situations is, I think, where we need to go as humanity. And this is one way to help develop those capacities. That’s the one side. I think we just need more and more of those kinds of capacities in order to address how we are in the world, and what we’re doing with the world.

On the other side, I just think if people were learning biology more in this way there would be more of a sense of the fact that this is a planet that we should be taking care of and not exploiting. There is also a danger in environmental classes, and in schools, of focusing children too early on all the problems we’re causing rather than first letting them get a sense for the wonders of the world, to let them fall in love with the world concretely. To know the world. I think this is especially important today where we are so screen focused. That we actually have hands-on, minds-on, senses-on experiences of the natural world. So that we’re rooted in the world. In this world. Not only rooted in Google and Facebook.

SA: This feels like the perfect transition into the last section of the book where you begin to tackle the condensation of the beings of the world into symbols, into things. For instance, the idea that we can determine or say, “The human being comes from the chimpanzee.” Why would we say such a thing? Do we even have evidence to say something like this? You begin to look at this idea that none of the specific traits in the human, none of the activity of the human, can you actually find in the fossil record of the chimpanzee. When we look at the fossil record, the picture only grows in complexity. It doesn’t become more clear. So, why would we say something like “human beings come from chimpanzees,” or, that “the frog comes from the tadpole,” when nothing of the frog exists within the tadpole? It sounds like this condensing of the educational experience to this symbolic, data driven process, it’s almost that that’s the only option. We can only really see the physical, skeletal remains, “that’s what we must come from.”

EH: It really separates out beings themselves. If you look at a fossil, you’re just looking at it like it’s a thing, not as a unique part of history and evolution.

SA: So then you start to explore a polarity. We have evidence of the created being in the form of, for instance, a fossil, or, for instance, when looking at a tadpole and just seeing, “Okay here’s a tadpole and here’s a fog.” Just the structure and, of course, there are mechanical realities to that, and you make sure to say you’re advocating for a science that doesn’t throw out research that is looking into things like the thyroid hormone. But on the other side of this polarity, there’s what you call, a “creative being, creative activity, agency, a being at work.” And anytime you focus on the one side of this polarity you start to lose the picture of what a being really is. Could you define and contextualize what these three phrases mean—creative activity, agency, a being-at-work?

CH: No, I can’t define them.

SA: I was expecting this! Because right after he says this, he says, “well, language isn’t important!” But, then these phrases appear over and over! They do seem indicative of a way of thinking that’s important.

“We’re forming, our bodies are forming through activity that achieves form, and the forms are always being re-formed. Every organismic process is like this.”

CH: You remember we talked about the beaver twelve days ago. I gave a portrayal of the beaver and then we looked at the teeth, the growing incisors, and how the incisors continue to grow, and at the same time they’re being worn down constantly as the animal is gnawing. I don’t remember who of you it was that realized, “the animal is a kind of activity.” It is “formed," but it’s also always “forming.” Think of what we just talked about this morning with human development in the bones, for instance the feet. We’re forming, our bodies are forming through activity that achieves form, and the forms are always being re-formed. Every organismic process is like this. The re-formation is slow, or it can be rapid, like in the development of the tadpole to the frog, where everything gets broken down and reorganized within a week. That this aquatic creature becomes that hopping creature. So this is where, if you follow the processes, you begin to see the animal is everywhere activity. It’s everywhere activity. Plants are activity in their own way too. It’s a different story, but we’re focusing on animals here. So, everywhere you can look, at every structure—as reflection of an activity. The skin is continually being replaced. We have all new red blood cells within 120 days. So, ongoing activity of the organism: that’s the one side. That’s what I’m calling agency, or using “creative activity,” which sometimes rubs people the wrong way—the creative part, I’ll come back to that in a second.

“Being-at-work” is a translation of Aristotle. That I got from an interesting newer translation of Aristotle by a person named Joe Sachs. He translates Aristotle’s term “energeia,” (where we get “energy” from) as “being at work.” An organism is a being-at-work. A being is a doing. To be a human being is to be a doing. To be a frog is to be a doing frog.

But, it’s also a formed frog. So, that’s what you were saying is the polarity, right? Because if I only think activity all the time, then I lose track of the fact that I wake up tomorrow and I’ve still got the same feet, I’ve got the same fingerprints. There’s something that stays somewhat the same. But, it’s staying the same, not because it’s some dead architecture, but because—not because, that’s not even the right word, it’s not a because—its “staying the same” is being continually created. And this is what Aristotle called “entelechy.” The entelechy, it’s something Sachs translates as “being-at-work-staying-itself.” It’s ingenious the way he translated this actually. It’s much more concrete than just saying “entelechy,” a term that might lead you to think of some “thing,” rather than a doing. The organism is an active being, always at work.